When I talk to many of my colleagues at CONICA and with contacts in our business segment, I very often ask them if the problems in the supply chain persist and if they expect them to be solved during this year 2022.

The unanimous answer is Yes for the first question and No Idea for the second.

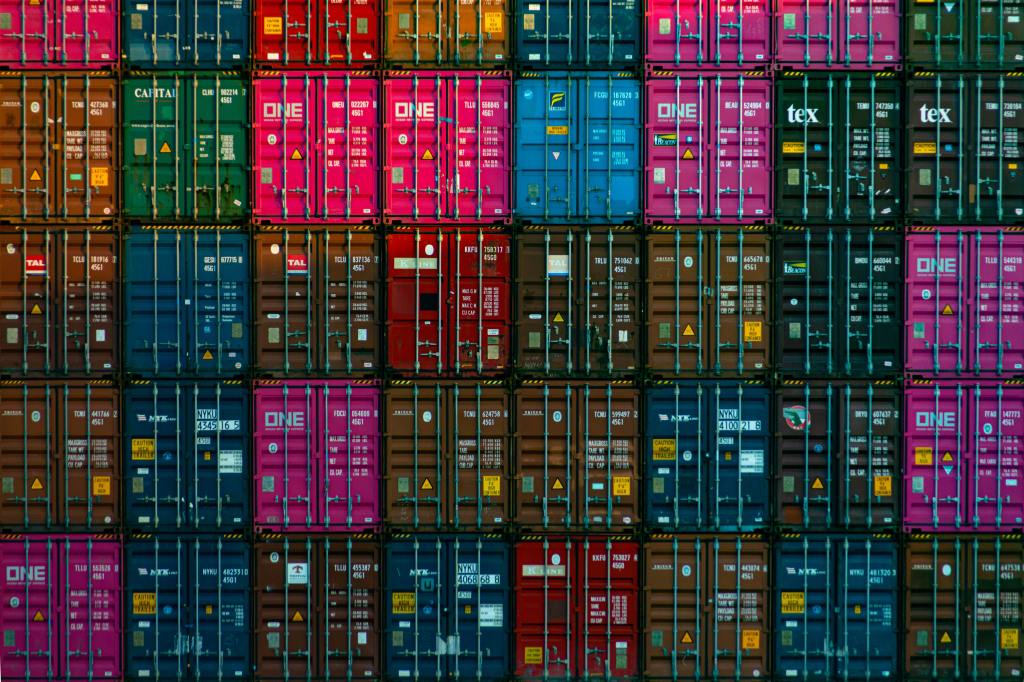

To find a more helpful answer to the second question I asked recently to some of my friends in the Barcelona Port and they explain me that movement of goods is rising here, but there are still a lot of problems and havoc at a lot of ports Worldwide with lack of containers and sea and road freight cost rising.

It looks like the disruption will continue during all this 2022 and a recent very interesting article at the New York Times from Peter S. Goodman explains some of the keys, and forecast that perhaps more than one year will be needed before the chaos subsides.

According to this article investment, technology, more ships, wharehouses and, an influx of truck drivers are required and none of this can be conjured quickly or cheaply and will be unlikely to happen in 2022.

Cheap and reliable shipping may no longer be taken as a given, forcing manufacturers to move production closer to customers. Prudent focus on extra capacity may also be needed.

The International Monetary Fund last week cited supply chain woes among other factors as it downgraded its forecast for global economic growth for 2022 to 4.4 percent from 4.9 percent.

The persistence of supply chain troubles in part result from how the coronavirus pandemic has accelerated trends that have been unfolding for decades. A lot of us thought would be a momentary phenomenon resulting from the pandemic but this has proven to be wrong. The pandemic has just highlighted the fragility of our supply chains.

Whereas major brands traditionally ship goods from factories around the world to central warehouses that supply retail outlets, the growth of e-commerce demands a far more complicated endeavor: Retailers must deliver individual orders to homes and businesses. We were not prepared for the new needs of warehouses, truck drivers, information systems, etc. this means.

The article of Peter S. Goodman makes a good chronology of facts that explains the problem:

- In the initial months of the spread of Covid-19, markets plunged and businesses laid off workers, manufacturers slashed orders for a vast array of goods on the assumption that health fears, lockdowns and diminished incomes would limit demand for their products. Using the same logic global shipping companies reduced service.

- The pandemic did not eliminate spending so much as shift it around. People stopped going to restaurants, sporting events and amusement parks, while directing their expenses to outfitting their homes for life under lockdown. They added treadmills to their basements, desk chairs to their bedroom, offices and video game consoles to their living rooms.

- As many of these goods were made in China, the surge of demand swamped the availability of shipping containers at ports in Asia, delaying transport.

- As ships arrived at destination ports, they carried more cargo than dockworkers and truck drivers could handle. Stacks of uncollected containers towered like monuments to globalization gone awry.

- The tightness in warehouses produced ports dysfunctions on the busiest ports. With limited room to stash goods offloaded from inbound vessels, containers have piled up on docks uncollected. That has prompted ports to force ships to float offshore for days and even weeks before they can unload.

- Over the last three months, container ships unloading goods have remained at ports for seven days on average, an increase of 4 percent compared with all of 2021 and 21 percent higher than at the start of the pandemic.

Some of this trends and effects may remain at the end of the pandemic but nobody can predict it reliably.

This New York Times article would change to YES the answer to my second question.

For our range of flooring chemical products at CONICA, we have been able to manage the raw materials shortages, especially for epoxy and aliphatic products but we had to deal with severe cost increases on raw materials, had to do several formulation changes to avoid shortages and make some unavoidable sales price increases.

At personal level, I planned to renew my Volvo that is more than 18 years old and has been around more than 350,000 km. I ordered a new full electric car 3 months ago and I will have to wait still a few more months to receive it due to the serious lack of chips and other components needed for car manufacturing. Damn Supply Chain disruptions!

Take care

References:

- Peter S. Goodman is a global economics correspondent, based in New York. @petersgoodman

- https://www.nytimes.com/2022/02/01/business/supply-chain-disruption.html